Jabberwocky

One of the most famous poems from the Alice books is “Jabberwocky”:

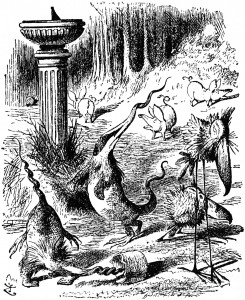

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!”

He took his vorpal sword in hand:

Long time the manxome foe he sought —

So rested he by the Tumtum tree,

And stood awhile in thought.

And as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.

“And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!”

He chortled in his joy.

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

The poem makes a lot of use of ‘portmanteaus’: a word that is made up of other words.

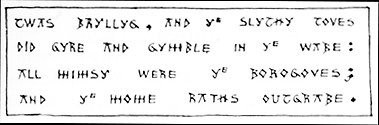

In the book, the first stanza of the poem is actually printed in mirrored font, but the whole poem is printed in normal font on the next page. Carroll may have considered printing it mirrorred in full, but abandoned the idea because it would become too costly. In 1868 he wrote to his publisher: “Have you any means, or can you find any, for printing a page or two in the next volume of Alice in reverse?”, and Macmillan responded that it would cost a great deal more to do so.

The slaying of the Jabberwock takes place on the very same island as where Carroll’s poem “The hunting of the Snark” takes place. The island is also frequented by the Jubjub and Bandersnatch. Carroll describers this in a letter to Mrs. Chataway, the mother of a child-friend (Gardner, “The definitive edition” 161).

How and when Jabberwocky was written

Dodgson made up the poem long before he published it in “Through the Looking-Glass and what Alice found there”. The first verse was also made up years before the rest of the poem.

The first stanza of the poem originally appeared in a 1855 edition of Mischmasch, a periodical that Carroll wrote and illustrated himself as a boy, for the amusement of his family. Carroll called it “Stanza of Anglo-Saxon Poetry” (Gardner, “The Annotated Alice”).

- “Bryllig”: (derived from the verb to bryl or broil). “the time of broiling dinner, i.e. the close of the afternoon”

- “Slythy”: (compounded of ‘slimy’ and ‘lithe’). “smooth and active”

- “Tove”: a species of Badger. They had smooth white hair, long hind legs, and short horns like a stag. lived chiefly on cheese.

- “Gyre”: verb (derived from ‘gyaour’ or ‘giaour’: “a dog”) “to scratch like a dog.”

- “Gymble”: (whence ‘gimblet’) to screw out holes in anything

- “Wabe”: (derived from the verb to ‘swab’ or ‘soak’) “the side of a hill” (from it’s being soaked by the rain)

- “Mimsy”: (whence ‘mimserable’ and ‘miserable’) ” unhappy”

- “Borogove”: an extinct kind of Parrot. They had no wings, beaks turned up, made their nests under sun-dials and lived on veal.

- “Mome”: (hence ‘solemome’ ‘solemone’ and ‘solemn’) “grave”

- “Rath”: a species of land turtle. Head erect, mouth like a shark, the front [crossed out] fore, legs curved out so that the animal walked on its knees, smooth green body, lived on swallows and oysters.

- “Outgrabe”: past tense of the verb to ‘outgribe’ (it is connected with the old verb to ‘grike’ or ‘shrike’, from which are derived “shriek” and “creak.”) “squeaked”

He further commented:

“Hence the literal English of the passage is:

“It was evening, and the smooth active badgers were scratching and boring holes in the hill side; all unhappy were the parrots, and the grave turtles squeaked out“.There were probably sun dials on the top of the hill, and the “borogoves” were afraid that their nests would be undermined. The hill was probably full of the nests of “raths”, which ran out squeaking with fear on hearing the “toves” scratching outside. This is an obscure, but yet deeply affecting, relic of ancient Poetry.

Carroll added the other verses a few years later during a verse-making game with his cousins.

Other explanations of the words

When publishing the complete poem in ‘Through the Looking-Glass’, Carroll had Humpty Dumpty explain it to Alice. Humpty Dumpty tells her the words mean the following:

“Brillig”: four o’clock in the afternoon — the time when you begin broiling things for dinner.

“Brillig”: four o’clock in the afternoon — the time when you begin broiling things for dinner.- “Slithy”: lithe and slimy. ‘Lithe’ is the same as ‘active’.

- “Toves”: curious creatures that are something like badgers, something like lizards, and something like corkscrews. They make their nests under sun-dials and live on cheese.

- “To gyre”: to go round and round like a gyroscope.

- “To gimble”: to make holes like a gimblet.

- “Wabe”: the grass-plot round a sun-dial. It is called like that because it goes a long way before it, and a long way behind it. And a long way beyond it on each side.

- “Mimsy”: flimsy and miserable

- “Borogove”: a thin shabby-looking bird with its feathers sticking out all round; something like a live mop.

- “Mome rath”: a ‘rath’ is a sort of green pig. Humpty Dumpty is not certain about the meaning of ‘mome’, but thinks it’s short for “from home”; meaning that they’d lost their way.

- “To outgrabe”: ‘outgribing’ is something between bellowing and whistling, with a kind of sneeze in the middle.

Carroll was often asked to explain the poem further. In a letter to child friend Maud Standen (1877) he wrote:

“I am afraid I can’t explain ‘vorpal blade’ for you – nor yet ‘tulgey wood’, but I did make an explanation once for ‘uffish thought’! It seemed to suggest a state of mind when the voice is gruffish, the manner roughish, and the temper huffish. Then again, as to ‘burble’ if you take the three verbs ‘bleat, murmur, and warble‘ then select the bits I have underlined, it certainly makes ‘burble’ though I am afraid I can’t distinctly remember having made it in that way.”

In the preface of ‘The Hunting of the Snark’, Carroll also explains of which words the word ‘frumious’ consists:

“[T]ake the two words ‘fuming’ and ‘furious’. Make up your mind that you will say both words, but leave it unsettled which you will say first. Now open your mouth and speak. If your thoughts incline ever so little towards ‘fuming’, you will say ‘fuming-furious’; if they turn, by even a hair’s breadth, towards ‘furious’, you will say ‘furious-fuming’; but if you have the rarest of gifts, a perfectly balanced mind, you will say ‘fruminous’. “

Around 1883 he also gave an explanation for the name ‘Jabberwock’, when a class in the Girls’ Latin School in Boston asked Carroll’s permission to name their school magazine ‘The Jabberwock’. He replied:

“[…] the Anglo-Saxon word ‘wocer’ or ‘wocor’ signifies ‘offspring’ or ‘fruit’. Taking ‘jabber’ in its ordinary acceptation of ‘excited and voluble discussion’, this would give the meaning of ‘the result of much excited and voluble discussion’.” (Collingwood 274)

According to Martin Gardner (Gardner, “The Anniversary Edition” 181), the word ‘whiffling’ is not a Carrolian word. It had a variety of meanings in his time, but usually referred to ‘blowing unsteadily in short puffs’, and therefore it became a slang term for being variable and evasive. In an earlier century ‘whiffling’ meant smoking and drinking.

‘Tum-tum’ apparantly was Victorian slang for the sound of a stringed instrument, when monotonously strummed.

The word ‘burble’ had long been used in England as a variant of ‘bubble’. Also, the word meant ‘to perplex, confuse, or muddle’.

‘Snickersnee’ is an old word for a large knife, and also means ‘to fight with a large knife’.

Also the word ‘beamish’ was not invented by Carroll. The Oxford English Dictionary traces it back to 1530 as a variant of ‘beaming’, meaning ‘shining brightly, radiant’.

Carroll’s made-up word ‘galumphing’ has entered the Oxford English Dictionary. It is attributed to Carroll and is defined as a combination of ‘gallop’ and ‘triumphant’, meaning ‘to march on exultantly with irregular bounding movements’.

Also the word ‘chortled’ made its way into this dictionary, where it is defined as ‘a blend of chuckle and snort’.

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master – – that’s all.”

Pronunciation

In the preface to ‘Through the Looking-Glass’, Carroll also gave some instructions for the pronunciation of the words:

“The new words, in the poem Jabberwocky (see p. 202), have given rise to some differences of opinion as to their pronunciation: so it may be well to give instructions on that point also. Pronounce ‘slithy’ as if it were the two words ‘sly, the’: make the ‘g’ hard in ‘gyre’ and ‘gimble’: and pronounce ‘rath’ to rhyme with ‘bath’.”

In his preface to ‘The Hunting of the Snark’, Carroll writes:

“The ‘i’ in ‘slithy’ is long, as in ‘writhe’; and ‘toves’ is pronounced so as to rhyme with ‘groves’. Again, the first ‘o’ in ‘borogoves’ is pronounced like the ‘o’ in ‘borrow’. I have heard people try to give it the sound of the ‘o’ in ‘worry’. Such is Human Perversity.”.

This word is also often being mispronounced or misspelled as ‘borogroves’

Is Jabberwocky a parody?

It is unclear whether ‘Jabberwocky’ is a parody of an earlier poem.

The first stanza of ‘Jabberwocky’ is reminiscent of lines from Shakespeare’s Hamlet (Act I, Sc. I – Horatio):

In the most high and palmy state of Rome,

A little ere the mightiest Julius fell,

The graves stood tenantless, and the sheeted dead

Did squeak and gibber in the Roman streets…’

Carroll may or may not consciousy have had it in mind when writing his stanza.

Roger Green (Green) suggests that Carroll may have had in mind a long German folk ballad called ‘Der Hirt des Riesengebürgs’, collected in 1818 by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué. The ballad tells the story of how a young shepherd slays a monstrous Griffin. Carroll’s cousin, Manella Bute, translated this poem to English in 1846 under the title ‘The Shepherd of the Giant Mountains’ and published it in ‘Sharpe’s London Magazin’ (March 7 and 21, 1846).

There is no direct similarity between the ballad and ‘Jabberwocky’; according to Green, it is ‘much in the feeling and the atmosphere; the parody is of general style and outlook’. Most notable is the line “Come to my heart, my true and gallant son!”

Works cited

Carroll, Lewis and Stuart Dodgson Collingwood. The Lewis Carroll Picture Book. T. Fisher Unwin, 1899.

Collingwood, Stuart. The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll. Project Gutenberg ebook, The Century Company, 1898, www.gutenberg.org/files/11483/11483-h/11483-h.htm.

Gardner, Martin. The Annotated Alice. Wings Books, 1998.

Gardner, Martin. The Annotated Alice. The definitive edition, Penguin Books, 2001.

Gardner, Martin. The Annotated Alice. 150th anniversary deluxe edition, W.W. Norton & Company, 2015.

Green, Roger Lancelyn. The Lewis Carroll Handbook. Oxford University Press, 1962.