Story origins

The story of Alice in Wonderland was inspired by many things out of Charles Dodgson’s environment: the author of ‘Alice in Wonderland’ referred to people and places he knew in his books. On this page you can read about them.

Origins of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

The White Rabbit

Dean Liddell, Alice’s father, could very well have been the White Rabbit, for the Dean was always running late too.

When Alice was a child, there was no west entrance to the Cathedral and the Dean would normally have had to leave the Deanery, walk along Tom Quad, around the Cloisters and into the Cathedral through the south door. Therefore he was notorious for being late for services.

The present Cathedral Garden then belonged to one of the Cannons who subsequently gave permission to the Dean to use the door as a short cut to the Cathedral.

The rabbit hole

It is said that the ‘Rabbit Hole’ can be found in the dining hall in Christ Church, Oxford.

Alice’s father would have dined at the High Table with other senior members of the college. After dinner the senior members did not drop down amongst the undergraduates but went through a panelled door to the left of the spot where Liddell’s portrait is now hanging. Behind this door is a very narrow spiral staircase which descends to the senior common room, then to a corridor which emerges in Tom Quad. Dean Liddell would use the staircase and appear in Tom Quad on his way home to the Deanery. So it is said that it was the inspiration for the Rabbit Hole.

However, as the spiral staircase behind the High Table in Hall was built in 1906, this claim can be doubted.

Off with his head!

At the time Carroll wrote “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, state-sanctioned executions were a subject of public controversy and heated debate in England. The Queen of Heart’s impulsive and absurd calls for beheadings may therefore be a way of ridiculing this longstanding practice of executions, and represent Carroll’s opinion on the matter (Abate).

The door to Wonderland

The door from the Deanery garden to the Cathedral Garden in Christ Church, Oxford, must have been the little door behind the curtain in the hallway.

The door to Wonderland; photo from https://www.chch.ox.ac.uk/blog/alice-day

The Dean’s Garden is the garden in which the Liddell sisters often played. The Cathedral Garden was a garden they were not allowed to enter – only the Dean was allowed to cross that garden, and so a young Alice would have seen her father disappearing through this door into a pretty garden, which she and her sisters could only see from the window of their nursery. This was a view also familiar to Dodgson from the period of time that he spent playing with the children in the nursery, and hence became the lovely garden Alice so desperately wanted to enter in the story.

On the far side of the Dean’s garden is the rear of the library. It was from the windows of this library that Dodgson, then in his post of Sub-librarian, was able to look down into the garden and first saw Alice playing with her brother and sisters. Because of his interest in photography he later approached the Dean’s wife and obtained permission to photograph the children.

The flower border along the Deanery Wall was planted with plants mentioned in ‘Through the Looking-Glass’.

Pictures from the same door, from the side of the Cathedral Garden:

Why the White Rabbit is always late

In the Tom Tower hangs the bell called Great Tom. At five past nine every night the bell strikes one hundred and one times, which represents the original number of Undergraduates at the college. On the last strike all the Junior members were expected to be back in college.

The reason for ringing at five past nine is that Oxford is five minutes west of Greenwich. Therefore, five past nine (Greenwich Time) is in fact nine o’clock in Oxford time.

Time was only standardized in Britain with the coming of the railways and the need for reliable time tables. Christ Church obviously decided that change was a bad thing and that they would retain to the old Oxford time. Still to this day the services times in the Cathedral are five minutes past the hour and the Formal Hall is held at 7.20 whereas all the other colleges dine at 7.15.

Even as a child Dodgson had a great interest in the railways and invented railway games using the timetables. Perhaps that is why the White Rabbit was always running late; he was a Christ Church White Rabbit.

Ada and Mabel

After Alice has fallen down the rabbit-hole and ponders who she is, she mentions the girls Ada and Mabel. In the original ‘Alice’s Adventures Under Ground’ tale, these names were Gertrude and Florence. Alice had two cousins with these names (Gertrude Frances Elizabeth Liddell and Florentia Emily Liddell) so this may have been a reference to them. Of course it wasn’t appropriate to do this in a mass-published book, so that’s probably why the names were altered (Demakos, “Part I”).

“Où est ma chatte?”

(Gardner, “Anniversary edition”)

Alice repeats the first sentence in her French lesson-book to the Mouse. Hugh O’Brien has found out that this lesson-book actually exists, and identified it as “La Bagatelle: Intended to introduce children of three or four years old to some knowledge of the French language” (1804) (O’Brien).

The queer-looking party of animals

At the end of the second chapter from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland it says: “There was a Duck, and a Dodo, a Lory and an Eaglet, and several other curious creatures”. The first part of the line refers to the author, his friend, and Alice’s sisters: all passengers who were with Alice in the boat when the story was first told to her. Lorina is the Lorry and Edith the Eaglet. The Duck is Canon Robinson Duckworth. The Dodo was Charles Dodgson, who had a slight stutter, which made him sometimes give his name as ‘Do-do-Dodgson’.

The proof that these last two nicknames were actually used, comes from Dodgson’s inscription in a 1886 facsimile edition of “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground”, which he dedicated to Robinson Duckworth. It read: “From the Dodo to the Duck”.

As Lorina was the oldest sibling, it explains the Lorry remarking to Alice: “I am older than you, and must know better”.

The ‘other curious creatures’ in this party represent the participants in an episode entered in Carroll’s diary on June 17, 1862. Carroll took his sisters Frances and Elizabeth, and his Aunt Lucy Lutwidge on a boating expedition, along with Reverend Duckworth and the three Liddell girls.

This is what Carroll wrote in his diary:

“June 17 (Tu). Expedition to Nuneham. Duckworth (of Trinity) and Ina, Alice and Edith came with us. We set out about 12.30 and got to Nuneham about 2: dined there, then walked in the park and set off for home about 4.30. About a mile above Nuneham heavy rain came on, and after bearing it a short time I settled that we had better leave the boat and walk: three miles of this drenched us all pretty well. I went on first with the children, as they could walk much faster than Elizabeth, and took them to the only house I knew in Sandford, Mrs. Broughton’s, where Ranken lodges. I left them with her to get their clothes dried, and went off to find a vehicle, but none was to be had there, so on the others arriving, Duckworth and I walked on to Iffley, whence we sent them a fly.”

Within the original manuscript appear many more details relating to this experience: the Dodo takes Alice, the Lorry, Eaglet and Duck to a house where they can dry instead of doing a caucusrace. Carroll later deleted it because he thought it would have little interest to anyone outside the circle of the individuals that were involved (Gardner, “Annotated Alice” 44).

Frances was Charles’ eldest sibling and four years his senior, and appeared to have an interest in history. Hence, she is probably represented by the Mouse, “who seemed to be a person of authority among them” and told the others the very dry story of William the Conqueror (Batey 40).

The Mouse’s tale

When the Mouse tells the driest thing he knows, he is quoting from Havilland Chepmell’s “Short Course of History”, 1862, pages 143-144. Chepmell’s book was one of the lesson books studied by the Liddell children (Gardner, “Annotated Alice” 46).

The caucus race

In England the term ‘caucus’ referred to a system of highly disciplined party organization by committees. It was often used as an abusive term for the organization of an opposing party. With the term ‘causus race’ Carroll may have poked fun at the committees, as committee members generally did a lot of running around in circles while they were getting nowhere.

The Lory and the Crab, and the Tweedle’s chapter

There seem to be several parallels between the book “Holiday House” by Catherine Sinclair (1839) and the Alice stories. Selwyn Goodacre mentions amongst others the following similarities (Goodacre):

“I was in the world long before you were born, and must know best: so hold your tongue.”

(said Mrs. Crabtree in Holiday House)

“Indeed, she had quite a long argument with the Lory, who at last turned sulky, and would only say, “I am older than you, and must know better.”

“…an old Crab took the opportunity of saying to her daughter, ‘Ah, my dear! Let this be a lesson never to lose your temper!’

‘Hold your tongue, Ma!’ said the young Crab, a little snappishly.”

(AAIW, chapter 3)

“…I shall say not another word about

THE PRODIGIOUS CAKE”

(In Holiday House, chapters II, III, IV, V, VI and VII all end with a repeat of the chapter title)

“…feeling sure that they must be

TWEEDLEDUM AND TWEEDLEDEE”

(The ending of chapter III of TTLG)

Mary Ann

In Lewis Carroll’s time, the name ‘Mary Ann’ was a euphemism for ‘servant girl’. Which implies that the White Rabbit may not actually have had a housemaid with that name (Roger Green in Gardner, “Anniversary edition”).

“Keep your temper”

The Caterpillar calls after Alice that he has something important to say, and then tells her: “Keep your temper”. This appears to be somewhat strange advice, as Alice was not even irritated at that moment. Melanie Bayley suggests that the word ‘temper’ does not relate to an emotional state, but to another meaning of the word: “the proportion in which qualities are mingled”. (According to Merriam-Webster: “the state of a substance with respect to certain desired qualities (such as hardness, elasticity, or workability” or “archaic: a suitable proportion or balance of qualities: a middle state between extremes“.)

So the Caterpillar could be telling Alice to keep her body in proportion, no matter what her size. That would be a precursor to her eating from the mushroom and accidentally giving herself a long neck (or such a short torso that her head bumps her feet). Apparently Alice did not understand the Caterpillar’s advice either (Bayley).

Alice’s long neck

In ‘Alice in Wonderland’, eating something causes Alice’s neck to stretch. This fireplace in the Hall (the largest college dining hall in Oxford) could very well have been the inspiration for this. Why? Just take a good look at the ‘firedogs’…

The Fish footman

In chapter 6 of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (‘Pig and Pepper’), Alice meets a talking fish. It is believed that this idea originated from an attraction Alice Liddell saw when she was at a fair.

The Cheshire Cat tree

This is said to be the tree in which the Cheshire Cat was seated. It is a Horse Chestnut tree. It grows in the Dean’s Garden of Christ Church, Oxford.

The Cheshire Cat

“To grin like a Cheshire Cat” was a common phrase in Carroll’s day. Its origin is not known. However, it could have originated from a sign painter in Cheshire, who painted grinning lions on the sign-boards of inns in the area.

Another explanation could be that at one time, Cheshire cheeses were molded in the shape of a grinning cat (Gardner, “Annotated Alice” 83).

Also, when you take a good look at the ‘Alice Window’ in Christ Church, Oxford, you can see 3 grinning animals at the top of the Liddell’s family arms. Perhaps this is what inspired Dodgson.

Finally, the Cheshire Cat might be inspired by a carving in St. Peter’s Church, in Croft-on-Tees, where Lewis Carroll’s father was rector. It is a sedilia – a seat for the clergy built into the wall – at one end of which is a carved stone face of a cat or lion. Seen from a pew it has a wide smile. But if you stand up, the grin seems to disappear, just as it eventually does in “Alice in Wonderland”. (discovery by Joel Birenbaum)

Finally, the Cheshire Cat might be inspired by a carving in St. Peter’s Church, in Croft-on-Tees, where Lewis Carroll’s father was rector. It is a sedilia – a seat for the clergy built into the wall – at one end of which is a carved stone face of a cat or lion. Seen from a pew it has a wide smile. But if you stand up, the grin seems to disappear, just as it eventually does in “Alice in Wonderland”. (discovery by Joel Birenbaum)

The Mad Hatter

Carroll might have based the Mad Hatter on Theophilus Carter, a former Christ Church servitor with ugly features and later a furniture dealer near Oxford. Carter was known in the area as the Mad Hatter, partly because he always wore a top hat at the back of his head and partly because of his eccentric ideas. He invented for example an ‘alarm clock bed’, which woke the sleeper by tossing him out. Perhaps this is why Carroll’s hatter is so concerned with the time and arousing the sleepy Dormouse? (Gardner, “The Annotated Alice” 93 and Batey 21)

However, according to Oxford local historian Mark Davies there is hardly any reason why the Hatter should be based on Carter. He thinks is more likely that the Hatter is Thomas Randall, a well-known local tailor who referred to himself as ‘a hatter’. Randall gave tea parties in his garden for children. Alice Liddell knew him and sometimes took his retriever Rover out for a walk. She mentioned frequent visits to his house, with great fondness (Davies, “Talk” 2).

Mad as a Hatter / Mad as a March Hare

The phrases ‘mad as a hatter’ and ‘mad as a march hare’ were also common in Carroll’s time.

‘Mad as a hare’ alludes to the crazy capers of the male hare during March, its rutting season.

‘Mad as a hatter’ probably owes its origin to the fact that hatters actually did go mad, because the mercury they used sometimes gave them mercury poisoning (Gardner, “Annotated Alice” 90).

However, there’s another theory about the origin of the phrase ‘mad as a hatter’ (snopes.simplenet.com):

[…] ” here’s the entry for ”‘Mad as a Hatter’ refers to madness or hatters” in the 1980 A Dictionary of Common Fallacies:

Lewis Carroll with his penchant for linguistic games presumably knew perfectly well that his “Mad Hatter’ meant ‘a venomous adder’, but since his readers may have been misled by Tenniel’s drawings, it should be pointed out that ‘mad’ meant ‘venomous’ and ‘hatter’ is a corruption of ‘adder’, or viper, so that the phrase ‘mad as an atter’ originally meant ‘as venomous as a viper’.

Here’s a much older citation of the same strip from a 1901 book:“In the Anglo-Saxon the word ‘mad’ was used as a synonym for violent, furious, angry, or venomous. In some parts of England and in the United States particularly, it is still used in this sense. ‘Atter’ was the Anglo-Saxon name for an adder, or viper. The proverbial saying has therefore probably no reference to hat-makers, but merely means ‘as venomous as an adder.’ The Germans call the viper ‘Natter.'” – Edwards’s Words, Facts, and Phrases.

In simpler terms, “mad as a hatter” was a play on words (with “adder” becoming “hatter”). Though the mercury/hatters/crazy explanation appears to fit the term, it fits only retrospectively — at the time Carroll coined the phrase, “mad” meant “venomous,” not “insane.” “

The Dormouse

Victorian children apparently actually had pet dormice, and kept them in old teapots filled with grass or hay. The Dormouse from Alice in Wonderland may have been modelled after Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s pet wombat, which had a habit of sleeping on the table. Carroll knew the Rossetti’s and occasionally visited them (Gardner, “Annotated Alice” 95).

Another possibility is that the Dormouse was inspired by Thomas Jones Prout. Prout was a Fellow of Christ Church from 1842, a Tutor from 1851 to 1861 and a Censor from 1857 to 1861, and lived at Christ Church for sixty-seven years. Prout was known for falling asleep in meetings, and apparently also had an interest in Frideswide’s well (the treacle well): according to the inscription on the well head, he had it rebuilt in 1874. (National Portrait Gallery)

The Mad Tea Party

In Victorian times, asylums opened their doors for ‘therapeutic entertainment’: events would be organized, including tea parties, that were open to visitors. It was thought to help with the re-socialisation of the patients, and it was a form of entertainent for the visitors. So the mad tea party scene may actually refer to a tea party with asylum clients!

Carroll must have been aware of this practice, especially because his uncle Robert Wilfred Skeffington Lutwidge was a Commissioner for the Commission in Lunacy, a state-supervised body for the inspection of lunatic asylums in Britain and Ireland. He appears to have visited such an asylum at least once.

As there were straw beds in some asylums, this may also explain the practice of drawing people with straw in on their heads (in this case, the March Hare’s head) to signify them being mad (Kohlt, “The stupidest Tea-Party” and Kohlt, “Alice in the asylum”).

Melanie Bayley (Bayley) believes that the Mad Tea Party is a reference to the work of mathematician William Rowan Hamilton:

“[H]is discovery of quaternions in 1843 was being hailed as an important milestone in abstract algebra, since they allowed rotations to be calculated algebraically.

[…] [Q]uaternions belong to a number system based on four terms […]. Hamilton spent years working with three terms – one for each dimension of space – but could only make them rotate in a plane. When he added the fourth, he got the three-dimensional rotation he was looking for […] “It seemed (and still seems) to me natural to connect this extra-spatial unit with the conception of time.”

Where geometry allowed the exploration of space, Hamilton believed, algebra allowed the investigation of “pure time”, a rather esoteric concept he had derived from Immanuel Kant that was meant to be a kind of Platonic ideal of time, distinct from the real time we humans experience. Other mathematicians were polite but cautious about this notion, believing pure time was a step too far.

The parallels between Hamilton’s maths and the Hatter’s tea party – or perhaps it should read “t-party” – are uncanny. Alice is now at a table with three strange characters: the Hatter, the March Hare and the Dormouse. The character Time, who has fallen out with the Hatter, is absent, and out of pique he won’t let the Hatter move the clocks past six.

Reading this scene with Hamilton’s maths in mind, the members of the Hatter’s tea party represent three terms of a quaternion, in which the all-important fourth term, time, is missing. Without Time, we are told, the characters are stuck at the tea table, constantly moving round to find clean cups and saucers.

Their movement around the table is reminiscent of Hamilton’s early attempts to calculate motion, which was limited to rotatations in a plane before he added time to the mix. Even when Alice joins the party, she can’t stop the Hatter, the Hare and the Dormouse shuffling round the table, because she’s not an extra-spatial unit like Time.

The Hatter’s nonsensical riddle in this scene – “Why is a raven like a writing desk?” – may more specifically target the theory of pure time. In the realm of pure time, Hamilton claimed, cause and effect are no longer linked, and the madness of the Hatter’s unanswerable question may reflect this.

Alice’s ensuing attempt to solve the riddle pokes fun at another aspect of quaternions: their multiplication is non-commutative, meaning that x × y is not the same as y × x. Alice’s answers are equally non-commutative. When the Hare tells her to “say what she means”, she replies that she does, “at least I mean what I say – that’s the same thing”. “Not the same thing a bit!” says the Hatter. “Why, you might just as well say that ‘I see what I eat’ is the same thing as ‘I eat what I see’!” […]

When the scene ends, the Hatter and the Hare are trying to put the Dormouse into the teapot. This could be their route to freedom. If they could only lose him, they could exist independently, as a complex number with two terms. Still mad, according to Dodgson, but free from an endless rotation around the table.”

The treacle well

At the tea party, the Dormouse mentions a treacle well. The idea of the treacle well originated from of the legend of St. Frideswide, a local princess. In an informative paper I received during my visit to Oxford, it said:

“This story of the well sounds like a piece of complete nonsense on the part of Dodgson, however it is, of course, complete logical, for one must always remember that when the story of Alice was first told, Dodgson was telling the story to a 10 year old girl. In order to keep her attention he had to talk about things that she knew and understood, as in the case of the treacle well.

The Frideswide Window tells the story of St. Frideswide and her flight from Prince Algar. […] Alice Liddell witnessed both the making and the installation of the window and was also familiar with the story of St. Frideswide. […]

The right hand of the window depicts the scene of Frideswide together with old women drawing water from a well, this water was then used by Frideswide to cure illness. This well still exists today (at St. Margaret’s Church, Binsey) and has always been known as a treacle well. The word treacle is an Anglo-Saxon word which means ‘cure all’ and this explains why the sisters at the bottom of the well were very unwell – had they been well then they would have had no need to go there in the first place.

It is known that Dodgson and Alice had visited the well several times and there is little doubt that it was the inspiration for the story told by the Dormouse.”

The sisters in the well: Elsie, Lacie and Tillie

The names of the three little sisters in the Treacle Well (Elsie Lacie and Tillie) also refer to the names of the three Liddell sisters: Elsie originated from the initials of Lorina Charlotte, Lacie is a transformation of Alice, and Tillie was short for Matilda, a name given to Edith by her sisters (Gardner, “Annotated Alice” 44 and 100).

There are even more references to them: see Cathy Dean’s text ‘The Duck and the Dodo: References in the Alice books to friends and family’.

The Duchess’s moral

The moral of the Duchess, “Take care of the sense and the sound will take care of themselves”, is an adaptation of an old English proverb; “Take care of the pence and the pounds will take care of themselves”.

“It’s as large as life, and twice as natural!” comes from another common phrase in Carroll’s time; “As large as life and quite as natural”. Apparently Carroll was the first to substitute ‘twice’ for ‘quite’, and this is now the usual phrasing in both England and the U.S. (Gardner, “Annotated Alice” 121 and 287).

Animal, vegetable or mineral?

When Alice meets the Duchess, the Duchess tells her:

“Flamingo’s and mustard both bite.”

Alice responds:

“Only mustard isn’t a bird. […] It’s a mineral, I think.”

In Through the Looking-Glass, the Lion asks Alice:

“Are you animal — vegetable — or mineral?”

“Animal, vegetable, mineral” was a popular Victorian parlor game. Players tried to guess what someone was thinking of. The first questions asked were traditionally: ‘Is it animal? Is it vegetable? Is it mineral?’ (Gardner, “Definitive edition”).

The Gryphon and the Mock Turtle

Batey (12-15) suggests that Carroll’s brothers Wilfred and Skeffington appear in the story as the Gryphon and the Mock Turtle. They occasionally joined him on boat trips with the Liddell children around 1858-1860, so, like Duckworth, they may have been incorporated into the earlier stories that were invented to amuse the children. Wilfred and Skeffington were both undergraduates at Christ Church – like the Gryphon and Mock Turtle, they went to the same school. Skeffington was a less talented student than Wilfred, and called ‘too stupid for Greek and for Latin’ in a poem that appeared in the magazine Carroll used to write to entertain his family members, which may explain why he ‘only took the regular course’. Like Carroll, Wilfred sometimes made drawings to accompany his stories and once drew a gryphon.

The Mock Turtle’s weeping may be based on the fact that marine turtles often appear to weep: it is actually a way of getting rid of the salt in the water. Lewis Carroll had an interest in zoology and was probably aware of this phenomenon.

The Gryphon’s occasional exclamation may be a joke about silent letters. According to Denis Crutch, the letter ‘j’ was being used als ‘i’ in the Old English style. In ‘rrh’ the ‘h’ is silent as in the words ‘myrrh’ and ‘catarrh’. So the sound ‘hjckrrh’ would effectively be ‘hic’, as in a hiccough, or ‘hiccup’ (Carroll, “Elucidating Alice”).

French, music and washing – extra

When the Mock Turtle talks about the courses he took, he mentions “French, music and washing – extra”. This phrase often appeared at boarding school bills, meaning that there was an extra charge for French and music, and for having one’s laundry done by the school (Gardner, “The Annotated Alice” 128).

The Conger Eel

The Conger Eel that came to teach ‘Drawling, Stretching, and Fainting in Coils’ is a reference to the art critic John Ruskin. He visited the Liddell family on a weekly basis, to teach the children drawing, sketching, and painting in oils (Gardner, “Anniversary edition” 115).

The date of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

When you read closely, you can discover the date on which ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’ took place. The date of the book is 4 May; Alice Liddell’s birthday.

We know that because of Alice’s remarks in chapters 6 and 7:

`the March Hare will be much the most interesting, and perhaps as this is May it won’t be raving mad–at least not so mad as it was in March.’

`What day of the month is it?’ he said, turning to Alice: he had taken his watch out of his pocket, and was looking at it uneasily, shaking it every now and then, and holding it to his ear.

Alice considered a little, and then said `The fourth.’

Alice Liddell was born in 1852, so she was ten in 1862 when the story was told, but her age in the story probably is seven. We know that because Through the Looking-Glass appears to take place a half year later (see further on this page) and she’s ‘exactly seven and one half years old’ in that book. The photograph which Carroll pasted at the end of the manuscript was also taken when she was seven (Gardner, “The Annotated Alice”).

The croquet game

Lewis Carroll made up many games to entertain Alice and her siblings. He invented amongst others a variant on the croquet game, called ‘Croquet Castles’.

The Liddell children actually played croquet with royalty. In May 1863, the royal couple visited Oxford. The festivities included a Grand Banquet at Christ Church (could the banquet in “Through the Looking-Glass” perhaps be based on this?), and a Deanery garden party. During their stay the Prince and Princess asked to play croquet with the Liddell children. In his diary, Carroll noted that “the children left at 4 to play croquet with the royal guests”. (Batey 80) At this point in time, however, Carroll had already completed writing his manuscript story, including the flamingo croquet game with the Queen of Hearts, so this event cannot have served as the inspiration for the game.

Mathematics in the story

As Charles Dodgson was a mathematics professor, he incorporated some mathematical puzzles and jokes into the story.

When Alice is in the hallway, trying to figure out her identity, she tries to recite the multiplication table:

4 x 5 = 12

4 x 6 = 13

4 x 7 =…

She notices it fails and comments that she’ll “never get to twenty at that rate”.

This could refer to the fact that multiplication tables traditionally stop with the twelves, so if you continue the progression until 4 x 12, you’ll only get to 19 (Gardner, “The Annotated Alice”).

A more complex theory, is that Alice’s calculations are actually valid when you use a number system with a base of respectively 18, 21, 24, and so on (always incrementing the base with 3):

4 x 5 = 12 (base of 18)

4 x 6 = 13 (base of 21)

4 x 7 = 14 (base of 24)

4 x 8 = 15 (base of 27)

4 x 9 = 16 (base of 30)

4 x 10 = 17 (base of 33)

4 x 11 = 18 (base of 36)

4 x 12 = 19 (base of 39)

However, then the system breaks down. In a number system with a base of 42, 4 x 13 is not 20. Therefore, Alice will indeed never get to twenty this way (Taylor).

For another example of possible mathematics in the story, see the section about the Mad Tea Party.

The number 42

The number 42 regularly appears in not only the ‘Alice’ books, but also in Carroll’s other works, like ‘The Hunting of the Snark’. It is not clear whether Carroll attached real significance to this number, or whether it was just a random number that he used as a recurring joke.

Examples of the use of the number 42 in the ‘Alice’ stories:

- “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” contains 42 illustrations. “Through the Looking-Glass and what Alice found there” was originally intended to have 42 illustrations as well. It must be noted, however, that initially Carroll commissioned Tenniel to only draw 12 illustrations for “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”. Later this became 20, then 24, then 34, and only eventually he decided on 42 illustations (Demakos, “Part II”).

- It is the number of ‘the oldest rule in the book’, according to the King of Hearts.

- Alice’s exclamation that she’ll “never get to twenty at that rate” can be mathematically explained if a number system with a base of 42 is used (see paragraph ‘mathematics in the story’ above).

- The White Queen gives her age as “one hundred and one, five months and a day”. This would be 37,044 days*. Assuming the Red Queen is the same age, the total of their two ages this is 74,088, which is 42 x 42 x 42 (Wakeling).

* We know the date the story took place: November 4th 1859. Counting back 101 years, 5 months and 1 day means that the White Queen was born on 3 June 1758. - The number 42 appears in the total of horses and soldiers that the White King sent in Through the Looking-Glass: 4207.

- Lewis Carroll would have been able to calculate the time it takes for a stone, dropped down a rabbit hole that happens to pass through the center of the earth, to reach the other side of the world. It would take… 42 minutes (Wakeling).

Repeating poetry

When Alice repeats poetry, like “How doth the little…”, she crosses her hands in her lap. All Victorian children were taught to cross hands while sitting, and fold them while standing, when repeating lessons. It was supposed to help them concentrate and prevent them from fidgeting (Carroll, “Elucidating Alice”).

Origins of Through the Looking-Glass

The opening scene

The opening scene in “Through the Looking-Glass” in which Alice ponders about the behaviour of her kittens, reflects a paragraph from an article in Blackwood’s Magazine, published in November 1846 (Tillotson, 1950):

‘It was the kitten that began it, and not the cat. It isn’t any use saying it was the cat, because I was there, and I saw it and know it; and if I don’t know it, how should anybody else be able to tell you about it, if you please? So I say again it was the kitten that began it, and the way it all happened was this.

‘There was a little bit, a small tiny string of blue worsted-no! I am wrong, for when I think again the string was pink-which was hanging down from a little ball that lay on the lap of a tall dark girl with lustrous eyes, who was looking into the fire as intently as if she expected to see a salamander in

the middle of it. [Meanwhile Huggs the old cat is watching through half-shut eyes] the movements of a smart little kitten [playing with a roll of paper, which pricks it]. And then the kitten put on a look of importance,

as if its feelings had been injured in the nicest points, and then walked up demurely to Huggs, and began to pat her whiskers, as if it wanted, which it probably did, to tell her all about it.’[There follows a long game with the worsted, the tall girl’s annoyance, and the intervention, in defence of the cat and against the kitten, of ‘a little child’ sitting on the other side of the fire.]

The Red Queen

When Carroll described his Red Queen in the article ‘Alice on the Stage‘, he described her as “formal and strict, yet not unkindly; pedantric to the tenth degree, the concentrated essences of all governesses”. Also, in earlier editions of the book, the Red Queen was being described as “She’s one of the thorny kind”. In later editions this was changed to “She’s one of the kind that has nine spikes, you know”, which referred to the spikes on a queen’s crown. Carroll may have decided to remove an in-joke: the Red Queen being the governess of the Liddell sisters, Miss Prickett. She was nicknamed “Pricks”.

The Rose and a Violet

The Rose and a Violet that Alice meets in the Garden of Live Flowers may refer two her two younger sisters, named Rhoda and Violet (Hunt, 69).

“It’s my opinion that you never think at all,” the Rose said, in a rather severe tone.

“I never saw anybody that looked stupider,” a Violet said, so suddenly, that Alice quite jumped; for it hadn’t spoken before.

The chessboard country

It is easy to visualise a ‘chessboard’ landscape: there must be many places on earth where you can stand on a hill and look out over square fields, divided by hedges and/or brooks. Mavis Batey suggests that Carroll was particularly inspired by the fields of Birdlip, as he mentions going there with Ina, Alice and Miss Prickett in his diary (entry April 4, 1863). (Batey 67)

(Photo’s: view from Crickley Hill over the Birdlip fields, found on TripAdvisor)

Jam tomorrow and jam yesterday

`You couldn’t have it if you did want it,’ the Queen said. `The rule is, jam to-morrow and jam yesterday — but never jam to-day.’

`It must come sometimes to “jam do-day,”‘ Alice objected.

`No, it can’t,’ said the Queen. `It’s jam every other day: to-day isn’t any other day, you know.’

In this passage, Carroll may be playing with the Latin word ‘iam’. The letters i and j are interchangeable in classic Latin. ‘Iam’ means now. This word is used in the past and future tense, but in the present tense the word for ‘now’ is ‘nunc’. So because you can never use ‘iam’ in the present, you’ll never have ‘jam to-day’!

It may also have to do with a second definition of the word ‘jam’. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, ‘jam’ does not only refer to the fruit spread for bread, but can also mean someting more figuratively: ‘something good or sweet, esp. with allusion to the use of sweets to hide the disagreeable taste of medicine … something pleasant promised or expected for the future, esp. something that one never receives’ (Jylkka).

The railway carriage

Apparently, the passage about Alice travelling by railway carriage used to contain an old lady. Carroll dropped her from the chapter after he received a letter from Tenniel on June 1, 1870, in which he made the following suggestion:

“I think that when the jump occurs in the railway scene you might very well make Alice lay hold of the goat’s beard as being the object nearest to her hand – instead of the old lady’s hair. The jerk would actually throw them together.

[…]”

(Gardner, “The Annotated Alice” 221)

Railway jokes

There are two jokes in the railway scene that may be missed if you don’t know the English phrases they are based on. “She must be labeled ‘Lass, with care'” refers to the fact that packages containing glass objects are commonly labeled ‘Glass, with care’. The line “She must go by post, as she’s got a head on her” refers to the fact that ‘head’ was a Victorian slang word, meaning postage stamp (as stamps had the head of the monarch on them) (Gardner, “Anniversary edition”).

Snap-dragon-fly

In Looking-Glass world Alice encounters a snap-dragon-fly, who’s body is made of plum-pudding, its wings of holly-leaves, and its head is a raisin burning in brandy. He makes his nest in a Christmas box.

This may seem a strange description, but it refers to ‘snapdragon’; a parlour game played at Christmas time in which children would try to ‘snatch raisins out of a dish of burning brandy and eat them while still alight’ (Jylkka).

Bread and butter

According to the American Edwin Marsden, some children are being taught to wisper ‘bread and butter, bread and butter’ whenever being circled by a wasp, bee, or other insect, to prevent getting stung. If this was also a customary in Victorian England, it may explain why the White Queen whispers this phrase when the is being scared by the monstrous crow.

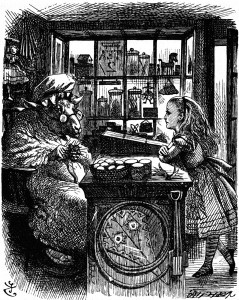

The Old Sheep Shop

In ‘Through the Looking-Glass’ Alice meets an old, knitting sheep in a shop. There was (and is) an actual shop in Oxford on which that part of the story was probably based.

Carroll and Alice must have often went to this shop, and even Tenniel may have visited it (Davies, 48). The shop was owned by John Millin and his wife Mary (nee Baker, 1802-1889) (Davies, “Shopping around” 49), who is said to have had a very bleaty voice and was always knitting. That may be why Carroll changed her into a knitting sheep.

Tenniel’s image of the shop shows it mirrored (although with fewer windows) – after all, Alice went through the looking-glass!

The sudden change of the shop into a river may be inspired by the occasional flooding of Oxford. The shop was one of the buildings prone to flooding. In December 1852, while Carroll was an Oxford undergraduate, there was a particularly severe flood. According to the London Illustrated News, there were numerous drowned carcasses, including those of sheep. (O’Connor).

Nowadays the shop is a souvenir shop, where you can buy lots of Alice in Wonderland things. You can find it at 83 Saint Aldgate’s Street, Oxford, which is directly across Christ Church.

The eggs from the Old Sheep Shop

The Sheep in Through the Looking-Glass tells Alice that if she buys two eggs, she has to eat them both. Alice decides to buy only one, for ‘they mightn’t be at all nice’. Undergraduates at Christ Church, in Carroll’s day, insisted that if you ordered one boiled egg for breakfast you usually received two, one good and one bad (Carroll, “Diaries” 176).

The Anglo-Saxon messengers

The messengers of the White King in ‘Through the Looking-Glass’, Haigha and Hatta, are the Mad Hatter and the March Hare from ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’. The Anglo-Saxon name ‘Haigha’ is pronounced as “Hayor”, which makes it sound like ‘hare’.

In his account of the Kings Messengers’ approach (Through the Looking-Glass), Carroll was poking fun at the very earnest Anglo-Saxon scholarship practiced at Oxford in his day, and both his and Tenniel’s renderings of the Messengers’ costume and ‘attitudes’ were almost certainly taken from one of the Anglo-Saxon manuscripts in Oxford’s Bodleian Library; the Caedmon Manuscript of the Junian codex.

Many of the words in ‘Jabberwocky’ are also related to Anglo-Saxon ones (Gardner, “The Annotated Alice” 279).

Magic tricks

Lewis Carroll had a fondness for amateur magic, and therefore references to magic tricks may have been added to the ‘Alice’ books. The Sheep’s standing up of eggs in the chapter “Wool and Water” was a common conjuring trick of the time. Also, Haigha’s extraction of a sandwich from his bag was a variation of the so-called Egg Bag Trick (Fisher 81).

“There’s glory for you!”

Wilbur Gaffney argues that Humpty Dumpty’s definition of ‘glory’ (“a nice knock-down argument”) may have been derived from a passage in a book from philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1599-1679):

“Sudden glory, is the passion which maketh those grimaces called LAUGHTER; and is caused either by some sudden act of their own, that pleaseth them [such as, obviously, coming out with a nice knock-down argument]; or by the apprehension of some deformed thing in another, by comparison whereof they suddenly applaud themselves.”

“I love my love with an H”

‘I love my love with an A’ was a popular parlor game in the Victorian time. The players recited the following lines:

“I love my love with an <A> because he’s: ….

I hate him because he’s: …

He took me to the Sign of the: …

And treated me with: …

His name’s: …

And he lives at: …”

At the end of each line the player had to make up a word beginning with the A, then the following player with a B, etc., until a player was unable to come up with a word. The wording of the lines varied (Gardner, “Anniversary edition”).

The White Knight

The White Knight represents Dodgson himself. This can be derived from the description (‘shaggy hair’, ‘gentle face and large mild eyes’), his many inventions, and his melancholy song. Also, on the underside of a hand-drawn game board Carroll once wrote: “Olive Butler, from the White Knight”, thereby identifying himself as the Knight (Stern), and when Carroll wrote “Isa’s Visit to Oxford” in 1888, he called himself ‘the Aged, Aged Man’, abbreviated as ‘the A.A.M.’ (Guiliano).

Therefore, when the White Knight says good-bye to Alice, who is going to become a Queen, Dodgson might be saying good-bye to Alice who is going to become a grown woman.

The leg of mutton

Carroll often parodied Victorian etiquette. An example is the scene in which Alice is being introduced to the Leg of Mutton:

“You look a little shy. Let me introduce you to that leg of mutton,” said the Red

Queen. “Alice–Mutton: Mutton–Alice.”

The mutton got up in the dish and made a little bow to Alice; and Alice returned the bow, not knowing whether to be frightened or amused.

“May I give you a slice?” she said, taking up the knife and fork and looking from one Queen to the other.

“Certainly not,” the Red Queen said very decidedly: “it isn’t etiquette to cut anyone you’ve been introduced to.”

One of the numerous rules which governed a proper Victorian lady’s behavior was the admonition against “cutting.” According to one etiquette guide, “A Lady should never ‘cut’ someone, that is to say, fail to acknowledge their presence after encountering them socially, unless it is absolutely necessary”.

Clearly, Carroll is poking fun at etiquette here both through the punning of the term “to cut” as well as the ridiculous bowing of the leg of mutton (Lim).

The date of Through the Looking-Glass

We can guess the date when the story ‘Through the Looking-Glass’ took place.

In the first chapter Alice says that ‘tomorrow’ there’ll be a bonfire. That means that it is November 4, one day before Guy Fawkes Day. This holiday was annually celebrated at Christ Church with a huge bonfire in Peckwater Quadrangle. Alice also tells the White Queen that she’s ‘seven and a half exactly’, so the continuation probably takes place a half year after the first story, which was dated on May 4th, and as the real Alice was born in 1852, the year must be 1859 (Gardner, “The Annotated Alice”).

Works cited

Abate, Michelle Ann. “Off with Their Heads!: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and the Anti-Gallows Movement”. Presentation as part of the session “The Endurance of Alice: Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice in Wonderland’ at 150”, Modern Language Association conference, Vancouver, 8-11 January 2015.

Batey, Mavis. The Adventures of Alice. The story behind the stories Lewis Carroll told. Macmillan Children’s Books, 1991.

Bayley, Melanie. “Alice’s Adventures in algebra: Wonderland solved”. Newscientist.com, 16 December 2009, www.newscientist.com/article/mg20427391-600-alices-adventures-in-algebra-wonderland-solved/.

Carroll, Lewis. Lewis Carroll’s Diaries – Volume 1. The Lewis Carroll Society, 1993.

Carroll, Lewis. Elucidating Alice. A Textual Commentary on Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Introduction and annotations by Selwyn Goodacre, Evertype, 2015.

Davies, Mark. “Shopping Around for the (Woolly and Watery) Facts: ‘Alice’s Shop'”. The Carrollian, nos. 35 & 36, December 2021.

Davies, Mark. Talk during the October meeting of the LCSNA. Described in: Morgan, Chris. “VirtuAlice 3: WCLD Radio Alice Is on the Air!” Knight Letter, Fall 2021, Volume III Issue 7, no. 107.

Demakos, Matt. “From Under Ground to Wonderland”. Knight Letter, volume II issue 18, no. 88, spring 2012.

Demakos, Matt. “From Under Ground to Wonderland Part II”. Knight Letter, volume II issue 19, no. 89, winter 2012.

Fisher, John. The magic of Lewis Carroll. Simon and Schuster, 1973.

Gaffney, Wilbur. “Humpty Dumpty and Heresy; Or, the Case of the Curate’s Egg”. Western Humanities Review, spring 1968.

Gardner, Martin. The Annotated Alice. Wings Books, 1998.

Gardner, Martin. The Annotated Alice. The definitive edition, Penguin Books, 2001.

Gardner, Martin. The Annotated Alice. 150th anniversary deluxe edition, W.W. Norton & Company, 2015.

Goodacre, Selwyn. Letter in “Leaves from the Deanery Garden”. The Knight Letter, volume 2 issue 8, no. 78.

Guiliano, Edward. Lewis Carroll – the worlds of his Alices. Edward Everett Root Publishers, 2019.

Hunt, Peter. The Making of Lewis Carroll’s Alice and the Invention of Wonderland. Bodleian Library, 2020.

Jylkka, Katja. “How little girls are like serpents, or, food and power in Lewis Carroll’s Alice books“. The Carrollian, issue 26, autumn 2010, published February 2015.

Kohlt, Franziska. “Alice in the asylum: Wonderland and the real mad tea parties of the Victorians”. The Conversation, 31 May 2016, theconversation.com/alice-in-the-asylum-wonderland-and-the-real-mad-tea-parties-of-the-victorians-60136

Kohlt, Franziska E.. “‘The Stupidest Tea-Party in All My Life’: Lewis Carroll and Victorian Psychiatric Practice”. Journal of Victorian Culture, volume 21, issue 2, 1 June 2016, pages 147–167.

Lim, Katherine A. “Alice–Mutton: Mutton–Alice: Social Parody in the Alice Books”. Victorian Web, Brown University, English 73, 1995, www.victorianweb.org/authors/carroll/lim.html.

National Portrait Gallery, “Thomas Jones Prout”. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person.php?LinkID=mp03669, accessed on 4 July 2020.

O’Brien, H.. “The French Lesson Book”, Notes and Queries, December 1963.

O’Connor, Michael. All in the golden afternoon – the origins of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The Lewis Carroll Society, White Stone Publishing, 2012.

snopes.simplenet.com/spoons/fracture/hatter.htm.

Stern, Jeffrey. “Carroll Identifies Himself at Last”. Jabberwocky, issue 74, summer/autumn 1990.

Taylor, A.L. The White Knight. Oliver and Boyd, 1952.

Tillotson, Kathleen. “Lewis Carroll and the Kitten on the Hearth“, The Magazine of the English Association, Vol VIII, no. 45, Autumn 1950, p. 136-138.

Wakeling, Edward. “Further findings about the number forty two”. Jabberwocky, vol. 17, no. 1 and 2, winter/spring 1988.