Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

I often receive the same questions by email. To save us both some trouble, here is a summary of the most-asked questions and my answers.

- Was Carroll on drugs when he wrote the Alice books, or are the books about drugs?

- Was Carroll a pedophile?

- Are the books and the pictures still copyright protected?

- I have a very old edition of the book. Do you know how much it is worth, or can you help me find the publishing date?

- Did Carroll propose to Alice? Why was there a break-up between Carroll and the Liddell’s? And what were the cut pages of Carroll’s diary about?

- The Mad Hatter has a card on his hat which says ‘10/6‘. What does it mean?

- So why is a raven like a writing desk?

- I’ve seen an Alice movie, but I cannot remember which one it was. Can you help me?

- Did the Dormouse actually say “Feed your head“, like they sing in Jefferson Airplane’s song “White Rabbit”?

- During the oyster scene (in the Disney movie) the ‘R’ in March flashes. Why?

- Can you explain the chess moves from Through the Looking-Glass?

- I heard the Alice books were banned in China. Is this true, and why?

- What font was used for the original editions of the books?

`I have answered three questions, and that is enough,’

Said his father; `don’t give yourself airs!

Do you think I can listen all day to such stuff?

Be off, or I’ll kick you down stairs!’

Q: Was Carroll on drugs when he wrote the Alice books, or are the books about drugs?

A: No. Carroll did not use drugs while writing the story. The larger part of the story was invented when he was on a boat trip with a friend, the real Alice and her sisters. He invented it while they rowed.

If Carroll was on drugs, the Alice books would probably be a series of rambling, disconnected, surrealist scenarios. But the Alice books are far from random. They contain some very intricate logic problems and very clever puns (not to mention Alice’s journey in “Through the Looking-Glass”, which follows the moves of a chess game), that could only be the work of a sharp mind in full control of its abilities.

Furthermore, you’ll find the same style of writing in the magazines he wrote in his youth, his various poems, stories, and other writings, and especially in the letters he wrote. If the Alice books were drug induced, the rest of his voluminous output would seem to suggest he was on drugs 24/7.

No evidence has ever been found that linked Carroll to recreational drug use. Even in his extensive diaries, Carroll has never made any reference to the use of drugs, except for one time when he took opium for a toothache (Burstein). Carroll wasn’t even a smoker – in 1886 he wrote to Henry Savile Clarke: “I’m not a smoker myself, but I allow my friends to smoke in my rooms.” (Cohen 293)

There is however one part in the book that may describe the use of drugs: the hookah smoking Caterpillar who advises Alice to eat from the mushroom. With the story Carroll made fun of all aspects of society, and it may be possible that he was reflecting the age with this part: In the Victorian era there were no drug laws like we know them now. Opium, cocaine, and laudanum (a painkiller that contained opium) were used for medicinal purposes, and could be obtained from a pharmacist (LSD was not yet invented at the time!). So in Carroll’s days it was not uncommon to experience the effect of being ‘high’, whether or not accidentally. The chapter about the hookah smoking caterpillar wasn’t part of the original story; it was one of the scenes he added later when he decided to publish the story and expanded it for that purpose.

However, it was definitely not Carroll’s intention to write a book about drugs: he wanted to entertain a little girl that he loved.

Q: Was Carroll a pedophile?

A: No. Carroll (whose real name was Dodgson) certainly liked little girls very much, and loved to entertain them and be in their presence. However, there is no evidence at all that he was sexually attracted to them. When his child-friends grew up, they told only positive stories about their warm friendship, and often the friendship continued during their adulthood. For example, Ethel Rowell, who was one of his private students and child friend, recalled:

“[…] In Mr. Dodgson’s presence I felt proud and humble, [and enjoyed the] grace conferred thus upon an ignorant schoolgirl by the magnanimity of a proud and very humble and very great and good man … He was so patient of all one’s limitations, so understanding, so infinitely kind.” (Cohen, 474)

Carroll loved to kiss his child-friends, but was very aware that this could be inappropriate if the girls were older. That he loved them because of their innocence, not in a sexual sense, and would never do anything against their own will or that of their parents, becomes clear from some of his letters, like this one which Carroll wrote to Ethel Rowell’s mother:

“The being entrusted with the care of Ethel for a day is such a great advance on mere acquintanceship, that I venture to ask if I may regard myself as on ‘kissing’ terms with her, as I am with many a girl-friend a great deal older than she is. Considering that – she being 17 and I 63 – I am quite old enough to be her grandfather, I hope you won’t think it a very out-of-the-way suggestion. Nevertheless, if I find you think it wiser that we should only shake hands, I shall not be in the least hurt. Of course I shall, unless I hear to the contrary, continue to shake hands only.” (Cohen, 187)

In 1880, he wrote:

“I promised a Snark to quite a new little friend, Lily Alice Godfrey, from New York: aged eight; but talked like a girl of fifteen or sixteen, and declined to be kissed on wishing goodbye, on the ground that she ‘never kissed gentlemen.’ It is rather painful to see the lovely simplicity of childhood so soon rubbed off: but I fear it is true that there are no children in America.” (Cohen, 188)

There was in fact gossip about him and his regular child friend visits, but he was not concerned about this at all. In a reply to a letter from his sister, who raised the question whether it was proper for him to permit young ladies, unescorted, to visit him at the seaside, he wrote:

[…] the opinion of ‘people’ in general is absolutely worthless as a test of right and wrong. The only two tests I now apply to such a question as having some particular girl-friend as a guest are, first, my own conscience, to settle whether I feel it to be entirely innocent and right, in the sight of God : secondly, the parents of my friend, to settle whether I have their full approval of what I do. You need not be shocked at my being spoken against. Anybody who is spoken about at all, is sure to be spoken against by somebody : and any action, however innocent in itself, is liable, and not at all unlikely, to be blamed by somebody. If you limit your actions in life to things that nobody can possibly find fault with, you will not do much…. (Carroll, 38)

Contrary to popular belief, Carroll did not only have child-friends. He also had lots of (female) adult friends. Only about 25% of all ‘children’ he was in contact with, was under the age of 14, and 25% was older than 18 years old (Peeters). Nor is it true that he disliked little boys.

Carroll was an avid photographer and besides his normal portraits, he did sometimes photograph children in the nude. However, in his time making nude photographs of children wasn’t uncommon. Many Victorian artists, like Julia Margaret Cameron and Oscar Rejlander, did studies of child-nudes; it was a trendy subject for the time and children were then seen as a symbol of innocence. These kind of photographs would be printed on greeting cards, or displayed on their parents mantelpieces (Wakeling). Carroll only took these photographs with permission from the children’s parents, often in their presence or that of a governess or nurse (O’Connor), and only if the children were completely at ease with it. He made sure that after his death those pictures were destroyed or returned to the children.

Q: Are the books and the pictures still copyright protected?

A: No. When the Alice books were published, they were copyright protected until 42 years after the first publication or 7 years after the author’s death, whichever was the longer. Later, the 1911 Act replaced the 1842 Copyright Act which extended the period to 50 years after the author’s death.

This means that the copyright on “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” subsisted until 1907 and that of “Through the Looking-Glass and what Alice found there” until 1948. As Tenniel died in 1914, his illustrations came into the public domain in 1964. This includes the colored illustrations for the “Nursery Alice”.

The text of the “Nursery Alice” came out of copyright in 1948. The copyright of the “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” manuscript facsimile expired in the same year.

Between Charles Dodgson’s (Lewis Carroll’s) death in 1898 and the expiration date of the copyright, publisher Macmillan owned the copyright to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Wilfred Dodgson, executor of Dodgson’s estate, sold it to them.

Notably the British Copyright act did not protect the stories and illustrations from being reproduced abroad. Many foreign publishers, for example in America, were therefore able to publish the story and Tenniel’s illustrations without permission from Dodgson, while they were still copyright protected in the UK.

Disney’s cartoon movie still remains in copyright. If you wish to use movie stills, video, audio, or anything else from the movie, you’ll need to ask permission from Disney.

Q: I have a very old edition of the book. Do you know how much it is worth, or can you help me find the publishing date?

A: No. Unfortunately there is no “price guide” to determine the current value of antiquarian books. The value of your edition depends on a lot of different factors, amongst others the state it is in. As I am not an antiquarian bookseller, I have no knowledge of appraising or dating old books, and can only advise you to visit a reputable antiquarian book dealer in your vicinity.

The original first edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Take a look at the site of the ABAA, where you can learn more about the appraisal of old books. Their FAQ-page offers a lot of useful information and you can also search for an expert in your vicinity! If you live outside the US, look for your own national antiquarian booksellers’ association. A professional antiquarian bookseller in the UK who is knowledgeable about Carroll related items is Dr. Jeffrey Stern. You can contact him through [email protected].

Please note that old or antique books aren’t necessarily valuable just because they are old. If your copy is not a first edition, or extremely rare because it has special features like an inscription from Lewis Carroll, it won’t be very valuable. If it’s in a bad condition, it won’t be valuable either.

Remember also that booksellers will seldom pay much more than 25% or 30% of a book’s current retail price, because of their own high costs. Auction houses will also ask for a percentage of the sale.

It is very unlikely that you own a first edition of the original book. The official first edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was printed by Macmillan and dated 1866. It has a red cloth cover. The recalled first edition is dated 1865. Only the latter is extremely rare and valuable, and will make you a millionaire if you own one: in 1998 a copy sold for $1,540,000; in 2016 a copy was valued between 2 and 3 million dollars (but remained unsold – and if I am correct, later sold for $1,800,000). The official first edition is less rare and could possibly fetch between between $2,000 and $3,000, depending on its state and other factors.

You can check the amounts that old Macmillan editions of the books went for at auctions in the past on my blog, and you can search the ABA website for the prices of antiquarian editions that are currently for sale.

There are also other publishers than Macmillan that published Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, so even though your edition states it is a first edition, it is most likely not the original first edition. If you want to check if your copy is an early first edition, visit this site, which describes all early first editions of Carroll’s writings. If you own an edition published by Henry Altemus, this site allows you to look up more information about it. Note that if you have a copy that looks like the red cloth first edition in the picture, but without a date, it may be a facsimile of the original first edition.

Q: Did Carroll propose to Alice? Why was there a break-up between Carroll and the Liddell’s? And what were the cut pages of Carroll’s diary about?

A: We don’t know for sure what the cut pages were about and why Carroll (Dodgson) suddenly broke off contact with the Liddell family. However, it is improbable that this was because he proposed to Alice.

We do know that, of the many child-friends Dodgson had, Alice was his favorite. In a letter to Alice when she was already an adult, in which he asked her permission to use the manuscript he gave her for publication, he wrote that she was his ‘ideal child-friend’:

“[…] my mental picture is as vivid as ever, of one who was, through so many years, my ideal child-friend. I have had scores of child-friends, since your time: but they have been quite a different thing.” (Dodgson)

However, relations between Dodgson and Alice’s parents were never optimal. This may be because Alice’s mother considered Dodgson’s social status to be too low, or because he often opposed to Dean Liddell’s way of running Christ Church College. Mrs. Liddell later on went so far as to burn all his early letters to Alice.

On October 28 1862, Dodgson wrote in his diaries being out of Mrs. Liddell’s good graces “ever since Lord Newry’s business”. This ‘business’ was a disagreement about lifting the college curfew for Lord Newry’s ball, which Dodgson opposed to (Cohen), while Mrs. Liddell was in favor of it. She hoped one of her daughters could marry Lord Newry (Gardner, XXVIII).

Still, his visits to the Deanery to see the Liddell sisters continued.

On June 25 1863, his diary records an expedition on the river involving the three girls, the Dean and Mrs Liddell, himself and two other young men. It is apparently a happy day, as Dodgson wrote in his diary: ““[…] after which the rest drove home in the carriage […] while Ina, Alice, Edith, and I (mirabile dictu!) walked down to [the] […] station, and so home by railway: a pleasant expedition, with a very pleasant conclusion”. Two days later, on June 27, Dodgson records writing to Mrs Liddell, “urging her either to send the children to be photographed…” The sentence remains unfinished, because it comes at the end of a page and the following page is missing, cut out by an unknown person. The word ‘either’ has also been crossed out, in a different ink, in an attempt to disguise the omission.

The record begins again on June 30. Dodgson notes that the Liddells are leaving for their summer holiday. They are not mentioned again until December 5, when he records meeting Mrs Liddell and the children at some theatricals, “but I held aloof from them, as I have done all this term” (Leach, “The Liddell Riddle”).

On 12 May 1864 he records in his diary: “During these last few days I have applied in vain for leave to take the children on the river, i.e. Alice, Edith and Rhoda; but Mrs Liddell will not let any come in fututre – rather superfluous caution.”

Apparently, around June 27-29 1863 an important change occurred in Dodgson’s relations with the Liddell family, but the description of it was purposely removed from the diary. This has led to a lot of speculation about what happened.

According to Karoline Leach (Leach, “In the shadow of the dreamchild”), several letters dating from 1930 have emerged from the personal archives of the Liddell family. They are from Lorina Liddell, then 81 years old, directed to Alice Liddell. Lorina writes Alice that Florence Becker Lennon visited her, because she was writing a biography about Charles Dodgson. Apparently Lennon speculated that Dodgson must have proposed to Alice, but was rejected, and that he was consequently banned from the Deanery. Lorina wrote to Alice: “I think she tried to see if Mr. Dodgson ever wanted to marry you!!”

When Lorina realised that Lennon wanted her to confirm this, she decided to go along with it, “as one had to give some reason for all intercourse ceasing” (according to the letter). She therefore confirmed that Dodgson’s manner toward Alice had become “too affectionate” as she grew older, and that “mother spoke to him about it, and that offended him so he ceased coming to visit us again”. But apparently this was not the true reason for the break-up. Lorina also wrote “Mr. Dodgson used to take you on his knee. I know I did not say that”, but it is rather unclear what Lorina meant with that. (Douglas-Fairhurst, 132)

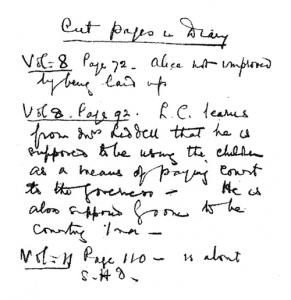

(Image source: Chang, “Seek it…” 16)

Besides these letters, a note has been found that seems to have been written by family members of Charles Dodgson. One side contains biographical notes about the Liddell daughters and Alice’s descendants. The other is headed ‘Cut Pages in Diary’ and contains summaries of the contents of three pages, two from Volume Eight and one from Volume Eleven. The second summary from Volume Eight is of the missing page. It reads:

“L.C. learns from Mrs Liddell that he is supposed to be using the children as a means of paying court to the governess – he is also supposed [unreadable – ‘soon’/’go on’/’by some’?] to be courting Ina.”

It is written in the hand of Lewis Carroll’s niece Violet Dodgson, who was co-guardian of the diaries from the early 1940s to the late 1960s.

Apparently, Violet must have gone through the diaries after Dodgson’s death, noting the pages to be cut for censoring and summarising their most important contents (Leach, “The Liddell Riddle”).

The governess mentioned in the note was Miss Prickett. There had indeed been gossip circulating about her and Dodgson back in 1857, but Dodgson described it in his diary as ‘so groundless a rumour’.

‘Ina’ is Lorina Liddell. However, whether Dodgson indeed courted Alice’s older sister, and whether this was the reason for the break-up, has never been confirmed by any evidence. The matter still remains a mystery.

Q: The Mad Hatter has a card on his hat which says ’10/6′. What does it mean?

A: The card is a price tag in ‘old’ English money: pounds, shillings and pennies, which was then written as l/s/d.

Lewis Carroll has explained the meaning of the tag in his ‘Nursery Alice‘:

The Hatter used to carry about hats to sell: and even the one that he’s got on his head is meant to be sold. You see it’s got its price marked on it – a “10” and a “6” – that means “ten shillings and sixpence.”

Ten shillings and six pennies (expressed in conversation as “Ten-and-Six”) was quite a large sum in the mid-1800’s.

Chris Somerville emailed me and amplificated:

The actual amount was significant also. Professional people (doctors, lawyers, architects etc) all charged fees, not in pounds but in guineas. One guinea was one pound plus one shilling. And while pounds were the currency of trade, guineas were the currency of the professions. We used to have a gold coin called, and valued at a guinea, and a smaller gold coin, a half guinea, valued at ten and six (10/6).

So the hat worn by the Mad Hatter was priced at half-a-guinea, signifying its superior style.

Q: So why is a raven like a writing desk?

A: Originally the riddle had no answer, but Carroll made one up later (see the Trivia section for details).

Many readers have invented their own answers ever since, including the most famous “because Poe wrote on both”, and my personal favorite “because there’s a B in both and an N in neither”.

Q: I’ve seen an Alice movie, but I cannot remember which one it was. Can you help me?

A: As my site is only about Carroll’s books and the Disney cartoon movie, you will not find a complete list of all Alice movies here. Take a look at the Internet Movie Database and you’ll find information about other movies (search for ‘alice in wonderland’, ‘through the looking-glass’ or the name of one of the actors). You can also buy various Alice movies in my webshop.

Q: Did the Dormouse actually say “Feed your head”, like they sing in Jefferson Airplane’s song “White Rabbit”?

A: No, The Dormouse never says that in the book, nor in Disney’s movie.

Either Jefferson Airplane made it up, or we should interpret the lyrics differently. Perhaps the line “Remember what the dormouse said” stands on its own, in stead of being connected to the next line, “Feed your head, feed your head”. The first line may be general advice about remembering what it said. It may even refer to a specific conversation in the chapter about the trial:

`Well, at any rate, the Dormouse said–‘ the Hatter went on, looking anxiously round to see if he would deny it too: but the Dormouse denied nothing, being fast asleep.

`After that,’ continued the Hatter, `I cut some more bread- and-butter–‘

`But what did the Dormouse say?’ one of the jury asked.

`That I can’t remember,’ said the Hatter.

Q: During the oyster scene (in the Disney movie) the ‘R’ in March flashes. Why?

A: The old saying is that one should only eat an oyster during the months spelled with an “R”. This was, historically, because summer months bring warmer waters and warmer waters bring spawning oysters and higher bacteria counts, which could be unhealthy or dangerous. Nowadays, with current cooling technology, there is nothing really wrong with eating a spawning oyster.

So Mother Oyster recognizes that March is a good month for eating oysters and as she doesn’t want her children to be eaten, she advises them to stay with her.

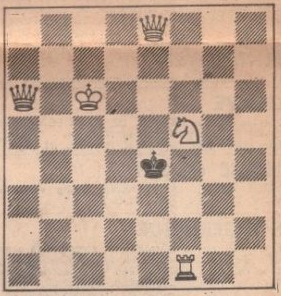

Q: Can you explain the chess moves from Through the Looking-Glass?

A: Yes, but you’ll have to accept that the moves in the story do not entirely adhere to the official rules of chess. Red and white do not alternate moves properly (white sometimes makes multiple moves in a row) and some of the moves listed do not represent actual moves of the pieces on the chessboard – sometimes a ‘move’ is just a conversation between characters, without any actual movement of the pieces on the board. However, Alice’s check mate of the Red King in the end is completely orthodox.

View the starting positions of the pieces.

There are two ways to describe the moves of the pieces:

The first way of notation is as follows: you describe the square the piece moves to by writing down the first letter of the piece that was on it when the game started (i.e. R when the piece goes to one of the squares in the column where the Rook started, B for the one of the Bishop, etc.). As there are two columns for most of the pieces, you should also put a Q or a K in front of it (if the piece moves to the left rook column, you add a Q because it is the side of the Queen. The right columns are those of the King). This isn’t necessary if it is the column of the Queen or King. Then you add the number of the square, counting from the side the piece started (if it is a red piece, you count from the top to the bottom, for a white piece, count from the bottom to the top).

This is the idea:

In that case the moves are:

- (…)

- W.Pawn to Q4

- (…)

- W.Pawn to Q5

- W.Pawn to Q6

- W.Pawn to Q7

- W.N.to K7

- W.Pawn to Q8

- (…)

- (…)

- W.Pawn to K8

- R.Q. to KR4

- W.Q. to QB4

- W.Q. to QB5

- W.Q. to KB8

- W.Q. to QB8

- R.N. to K2

- W.N. to KB5

- R.Q. to K1

- (…)

- W.Q. to QR6

The other notation is as follows. Numbers and letters are assigned to the squares, as in the picture. You start by naming the piece that moves (except if it’s a pawn). Then you describe the starting position of the piece and the ending position.

In that case the moves are:

- (…)

- d2 – d4

- (…)

- d4 – d5

- d5 – d6

- d6 – d7

- WN f5 x e7

- d7 – d8

- (…)

- (…)

- d8 x e8

- RQ e2 – h5

- WQ c1 – c4

- WQ c4 – c5

- WQ c5 – f8

- WQ f8 – c8

- RN g8 – e7

- WN e7 – f5

- RQ h5 – e8

- (…)

- WQ c8 – a6

Or perhaps the following description of all ‘moves’ (translated from a newspaper article by C. Orbaan) is more easy to follow:

- Conversation of Alice with the Red Queen, who is standing next to her.

- The Red Queen runs from e2 to h5.

- Alice moves from d2 (through d3 by railway) to d4, where she meets Tweedledum & Tweedledee.

- The White Queen travels from c1 to c4.

- Alice meets the White Queen and has a conversation with her.

- The White Queen moves from c4 to c5, thereby transforming into a sheep.

- Alice moves on from d4 to d5.

- The White Queen moves from c5 to f8.

- Alice continues from d5 to d6, where she meets Humpty Dumpty.

- The White Queen moves from f8 to c8 while fleeing for the Red Knight (although there is no real reason for doing so).

- Alice moves from d6 to d7 while walking through the woods where things have no names.

- The Red Knight becomes threatening by moving from g8 to e7.

- The White Knight beats the Red Knight after a fight: WNf5xe7. Alice is now standing next to the White Knight.

- The White Knight says goodbye to Alice and moves back from e7 to f5.

- By moving from d7 to d8, Alice becomes a queen.

- The Red Queen moves from h5 to e8 to question Alice. She hereby effectively threatens the White Queen, although this is not clear in the story.

- After the questioning of Alice by both Queens, she now officially becomes a queen.

- The ‘castling of the Queens’ occurs. In chess, castling means that the king is shifted two squares toward a rook of the same color on the same rank, and the rook is transferred to the square crossed by the king. However, in the story, no actual movement occurs on the chessboard. According to Carroll (in a 1890 preface to the book) he tells us this is just a way of saying that the Queens enter the castle.

- Alice ‘castles’. Again, there is no actual move on the chessboard, it merely means she is entering the party.

- The White Queen moves from c8 to a6, thereby giving Alice the opportunity to make her final move.

- Queen Alice captures the Red Queen by moving to e8 and at the same time checkmates the Red King: d8 x e8.

The final positions would be:

Q: I heard the Alice books were banned in China. Is this true, and why?

A: It is unclear whether this is true or merely a wide spread rumour.

The story about the book being banned because ‘it was degrading for human beings to converse with animals’ was spread by a New York Times column called “Topics of the Times”, by an anonymous writer in 1931, where he claimed the Alice in Wonderland book was banned in the Province of Hunan. It was then repeated as a fact by other media and books, causing the story to spread. The story was based on the following:

In 1931, according to a Shanghai newspaper, Chairman of the Hunan Provincial Government Ho Chien accused primary school textbooks of not conforming to Communist standards. He found it absurd that animals were being transformed into human-language-speaking creatures and were given respectful forms of address. He said: “School textbooks that are inadequately difficult or whose theories are simplistic but impractical must be destroyed by fire”.

This, however, was his personal request, but it is not proven to be actually executed. Neither did he specifically mention “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”. So it may have been misinterpreted by the author of the New York Times column.

However, the author of the Chinese translation, Y.R. Chao, confirmed the banning in the last paragraph of chapter 16 in “Family of Chaos”, an autobiography written by his wife, which he translated into English (notably the confirmation was not included in the original Chinese version):

[…] This time, he [Y.R. Chao] found that his translation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland had been prohibited by Governor Ho Chien because it encouraged superstition. However, that only lasted a year or two.”

As Ho Chien became governor in 1929, the book may therefore have been banned in China between 1929 and 1931 – not in 1931 as the New York Times stated: in that year, another edition of the translation was officially issued in China, which would not have been possible if it had (still) been banned.

(Burstein and Feng and Chang)

Q: What font was used for the original editions of the books?

A: The exact font that was used by Macmillan doesn’t currently exist anymore, but the font comes very close to the currently available ‘Monotype Modern’. This is the font VolumeOne used when producing a typographically accurate reproduction of the first edition.

Monotype Modern, known in metal as Modern Extended, was originally adapted from 19th century types designed by British foundry Miller & Richard. It represents not only the nearest known PostScript match to the original type used for this book, but also is probably the only truly authoritative example of the standard English modern to survive to PostScript.

(Ames)

Works Cited

Ames, Patrick. Colofon to the BookVirtual Edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, November 2000, https://www.adobe.com/be_en/active-use/pdf/Alice_in_Wonderland.pdf.

Burstein, Mark. “…of the mushroom”. Knight Letter, volume III issue 1, no. 100, spring 2018.

Burstein, Mark and Zongxin Feng. “Another ben trovato”. Knight Letter, volume II issue 24, no. 94, spring 2015.

Carroll, Lewis and Martin Gardner (introduction and notes). The Annotated Snark. Penguin Books, 1977.

Chang, Howard. “Further Evidence on the Banning of a Chinese Wonderland”. Knight Letter, volume II issue 28, no. 98, spring 2017.

Chang, Howard. “Seek it with a thimble”. Knight Letter, volume II issue 22, no. 92, spring 2014.

Cohen, Morton N.. Lewis Carroll: a biography. Vintage Books, 1996.

Dodgson, Charles Ludwidge. Letter to Alice Hargreaves, 1885. Made available by The New York Public Library: Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature.

Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert. The Story of Alice. Lewis Carroll and the Secret History of Wonderland. Vintage, 2016.

Gardner, Martin. The Annotated Alice. The definitive edition, Penguin Books, 2001.

Leach, Karoline. “The Liddell Riddle“. Extract from Times Literary Supplement, May 3 1996, www.lewiscarroll.org/leachnote.html.

Leach, Karoline. In the Shadow of the Dreamchild. The myth and reality of Lewis Carroll. Peter Owen Publishers, 1999.

O’Connor, Michael. All in the golden afternoon – the origins of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. White Stone Publishing, The Lewis Carroll Society, 2012.

Peeters, Carel. Het wonderland van Lewis Carroll. De Harmonie, 2013.

Wakeling, Edward. “The right of reply. Eight or nine wise words about documentary-making…”. Bandersnatch, issue 166, March 2015.